Background

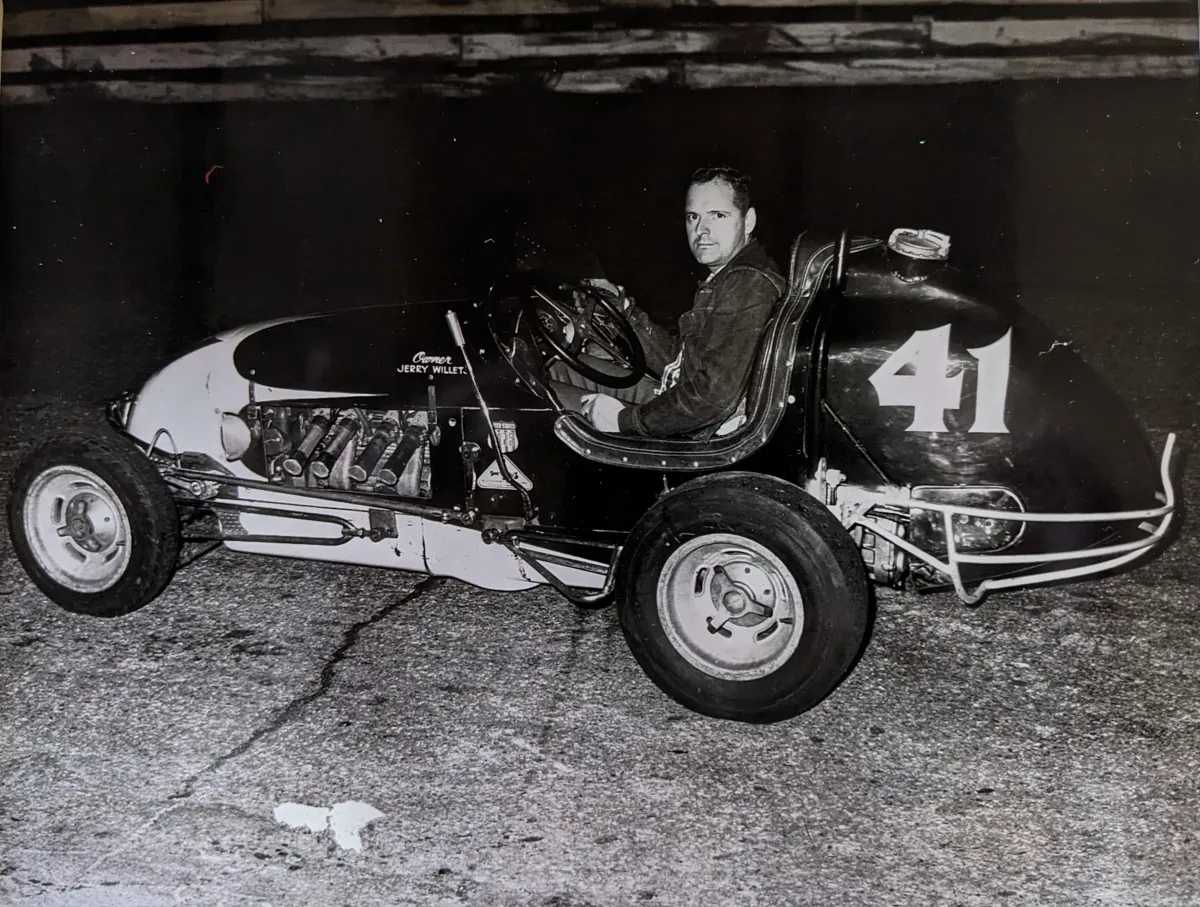

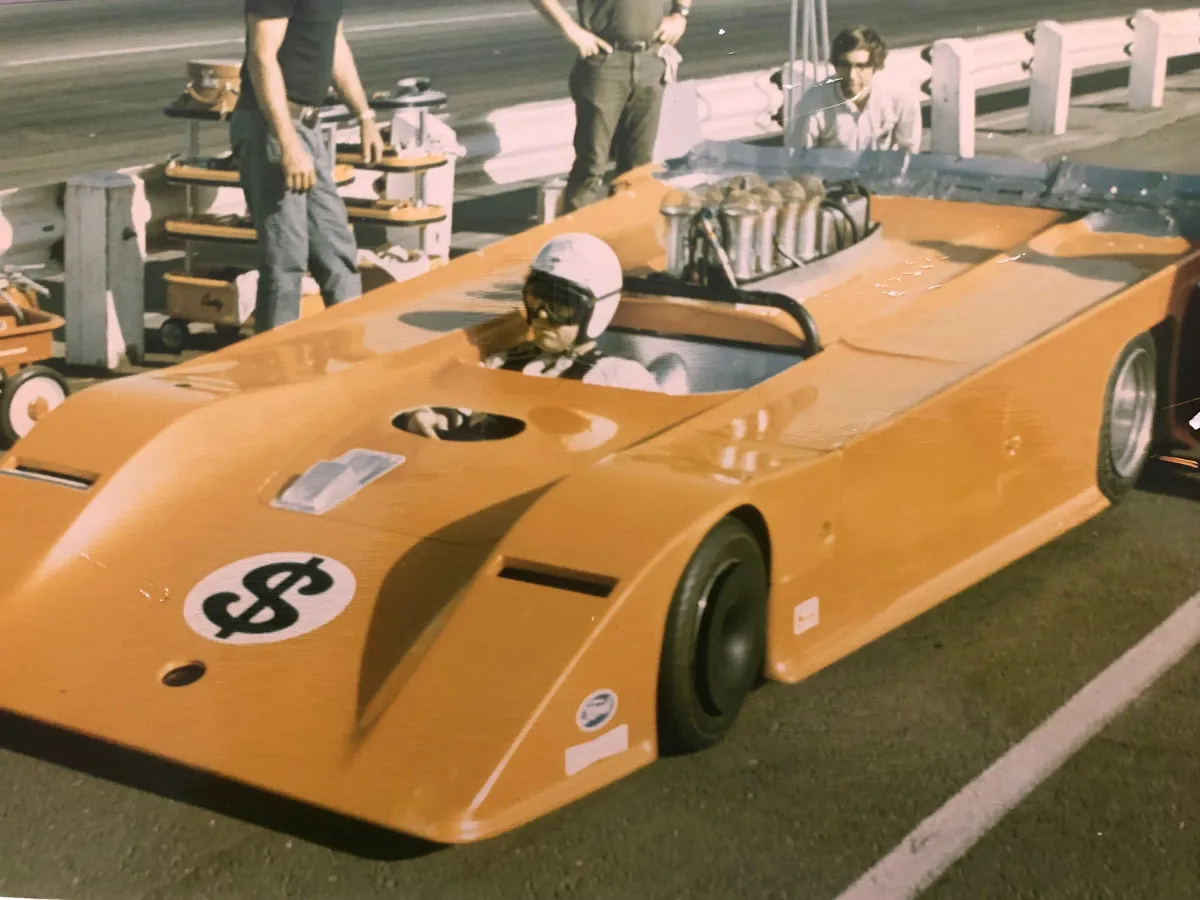

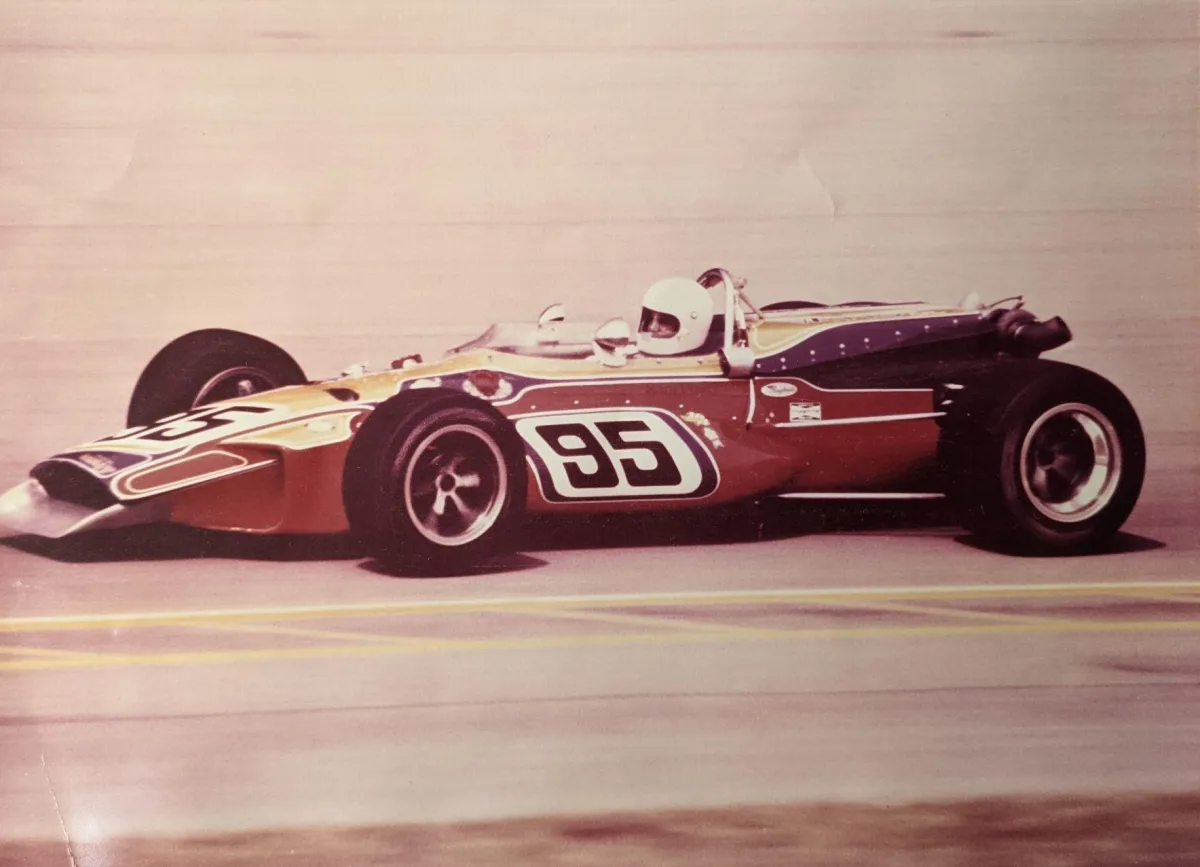

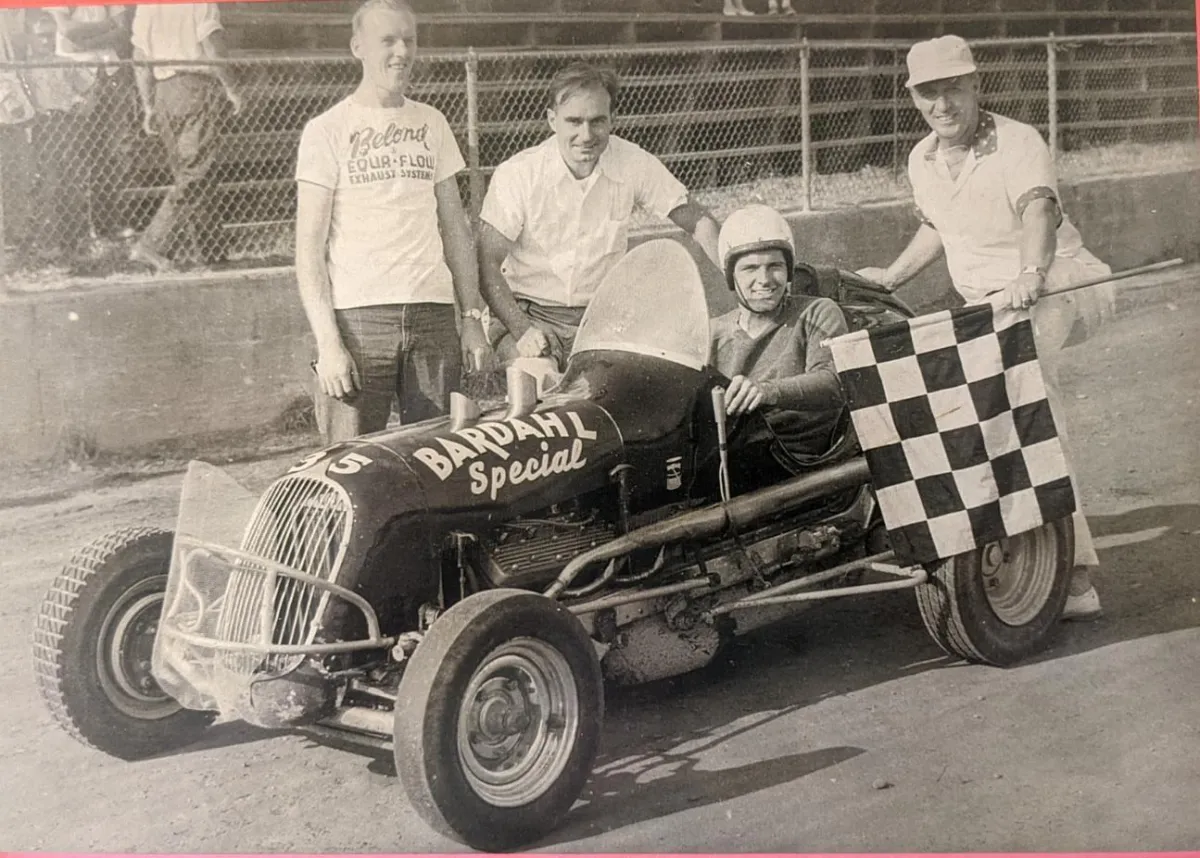

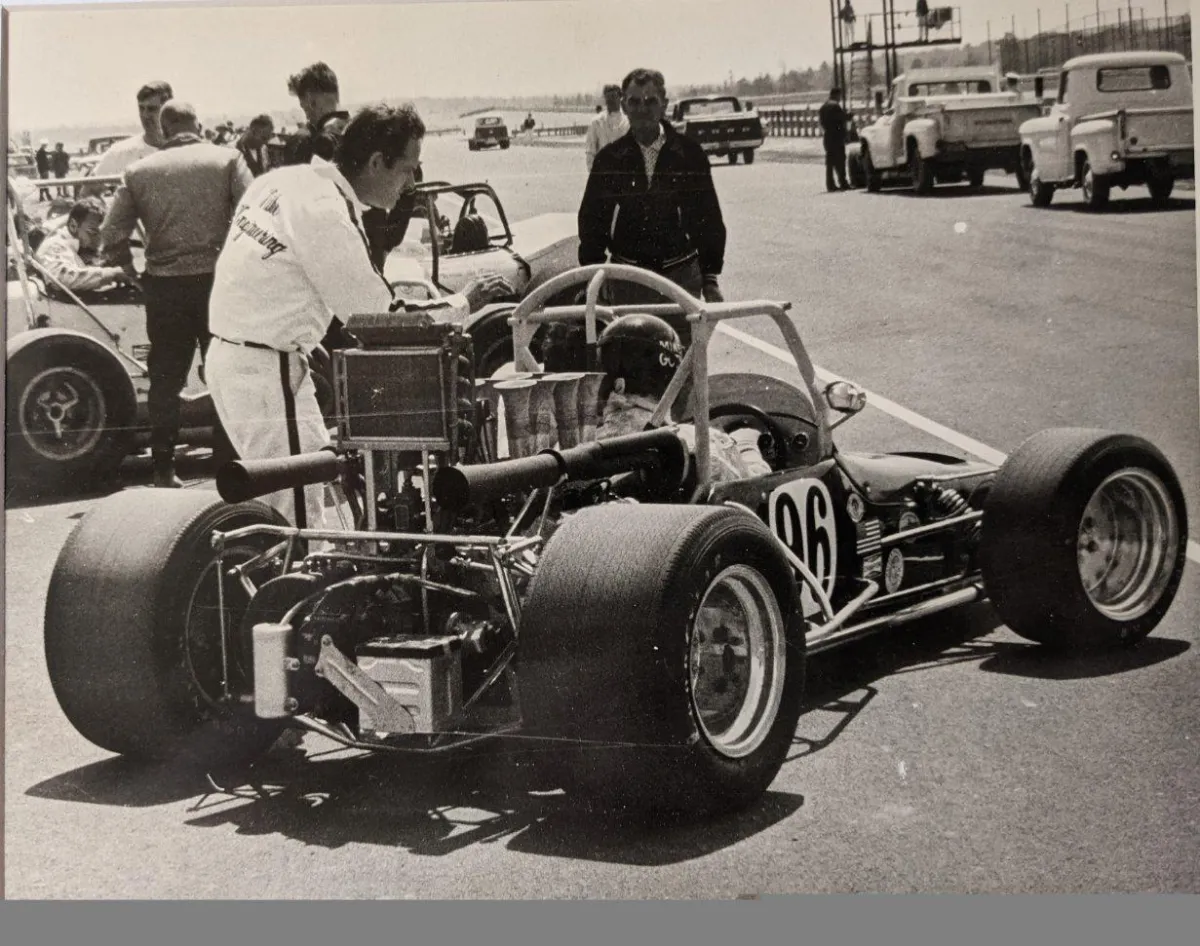

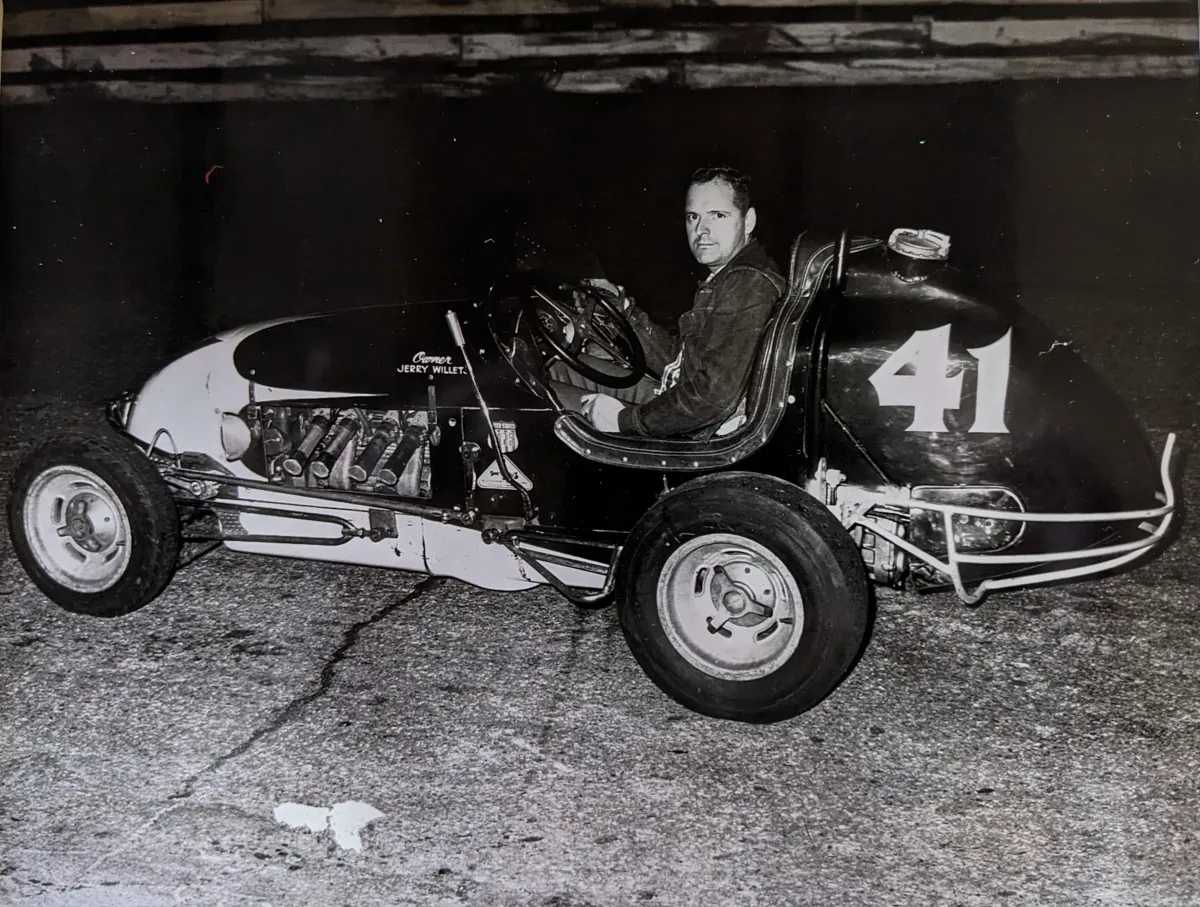

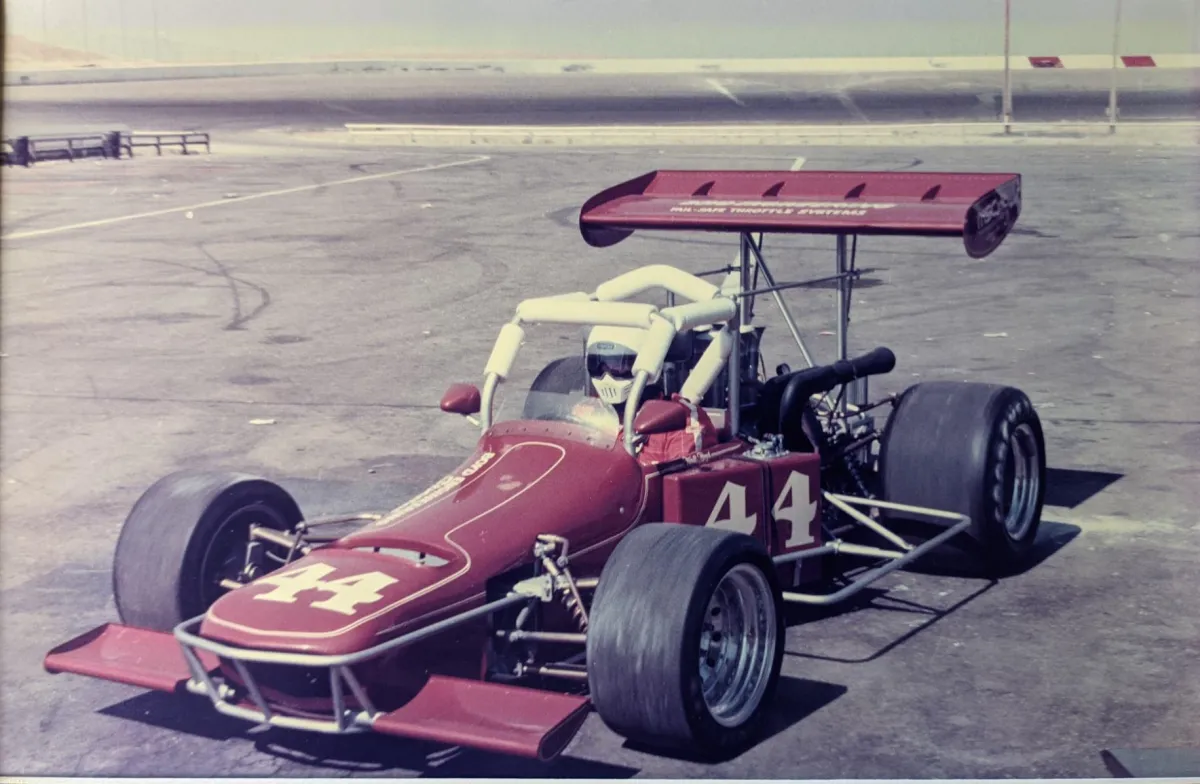

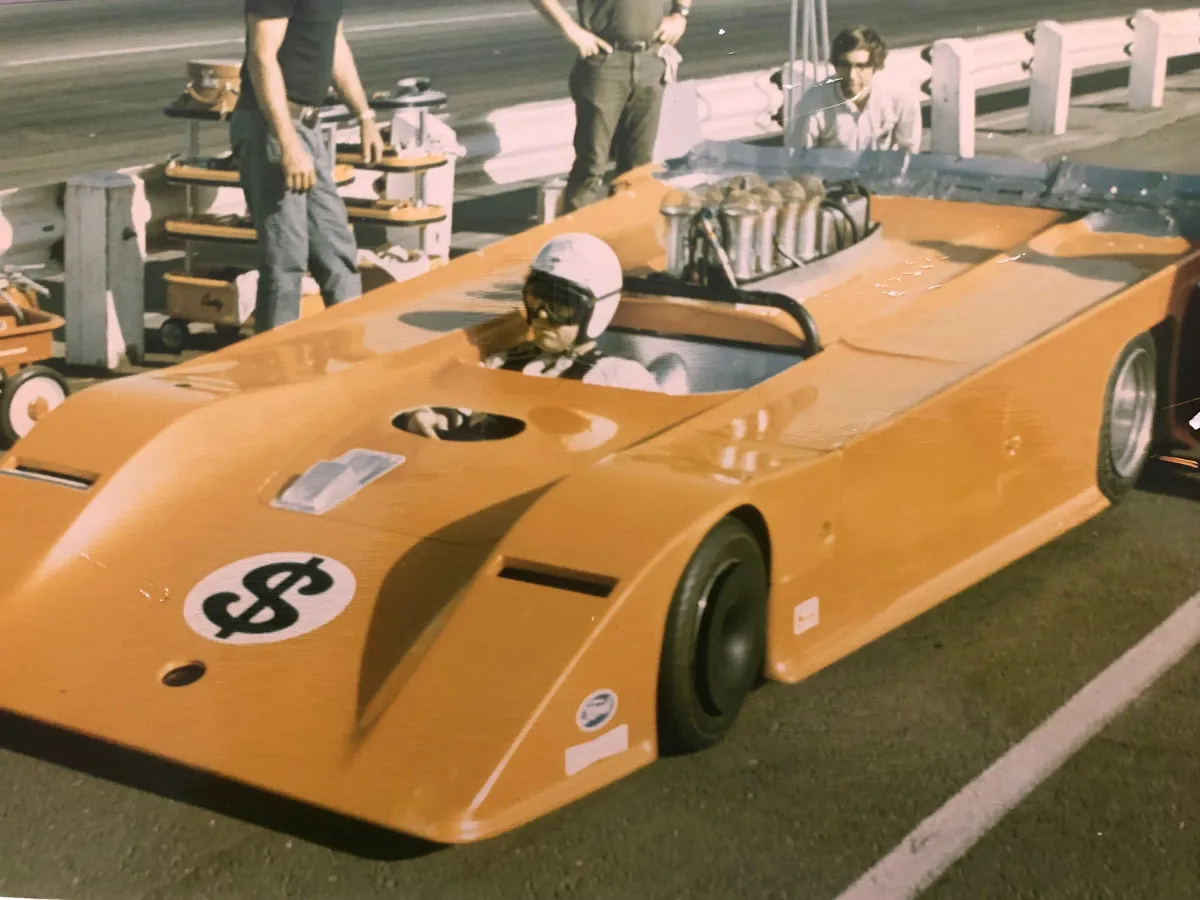

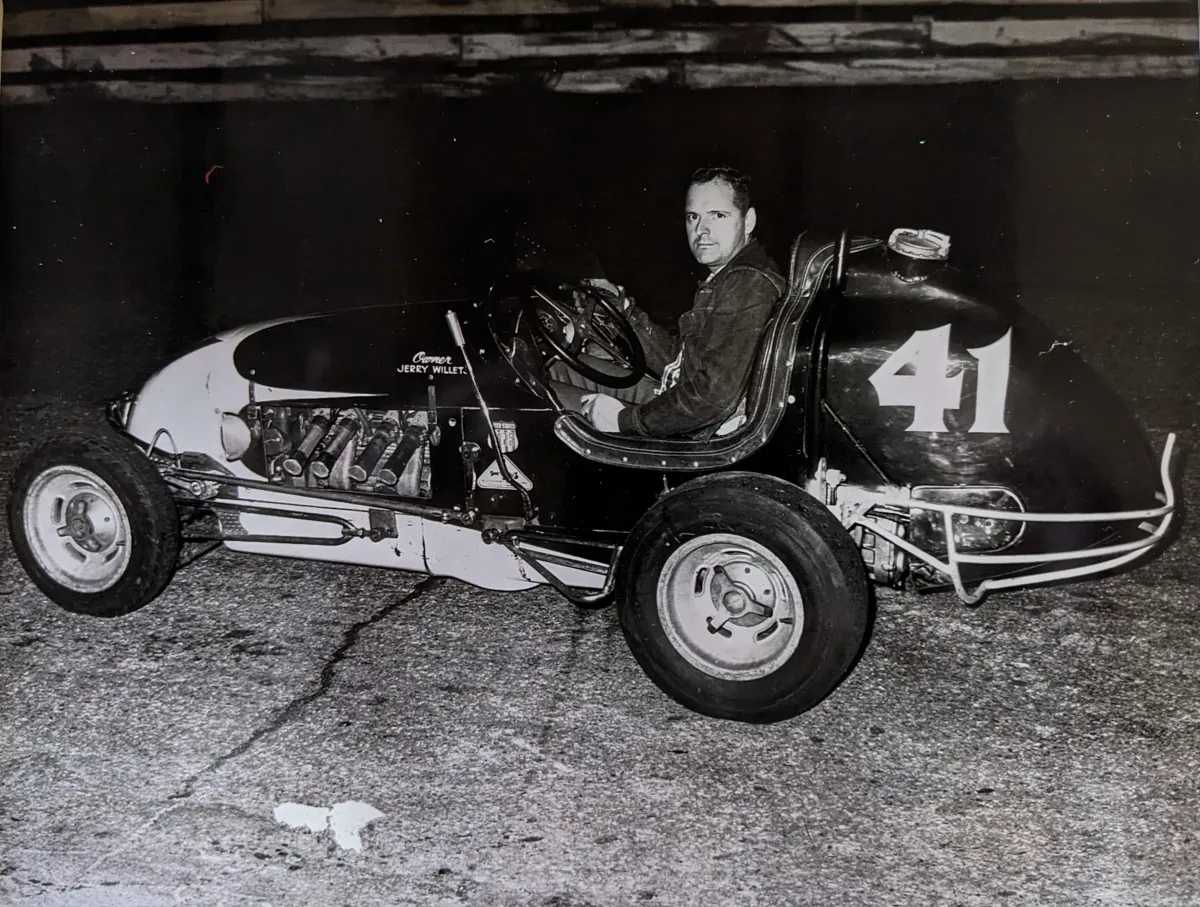

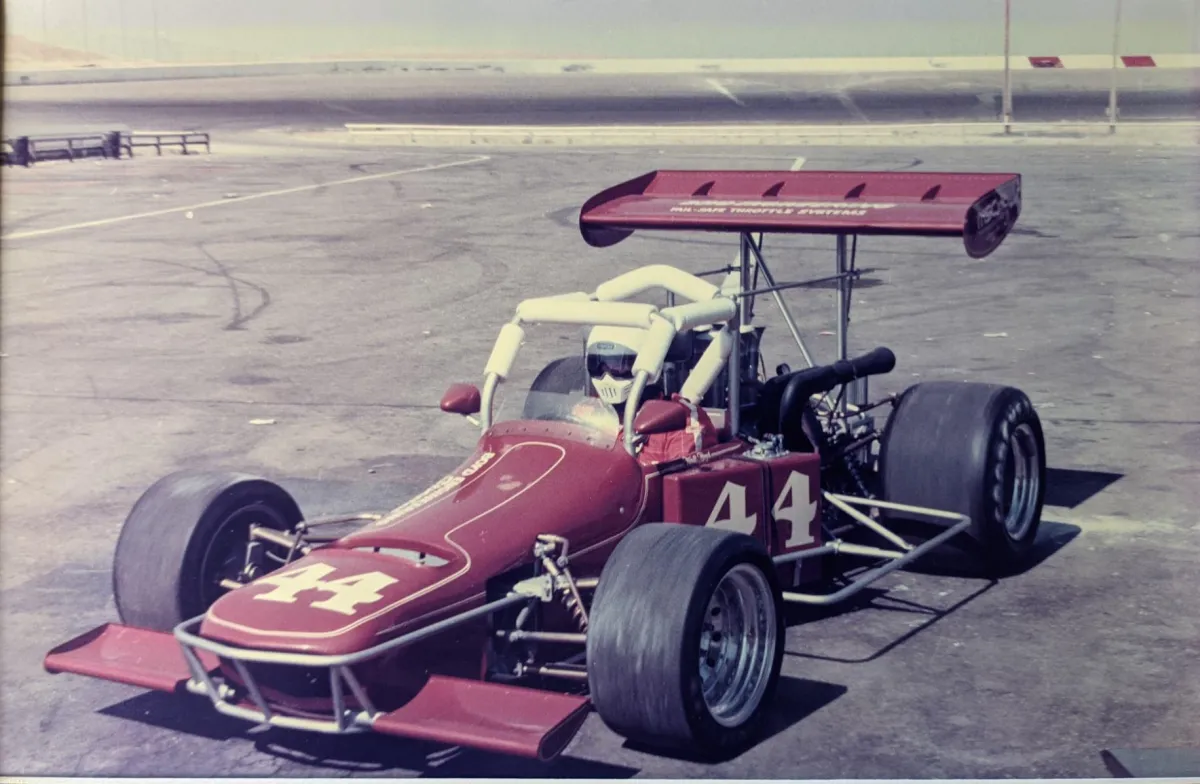

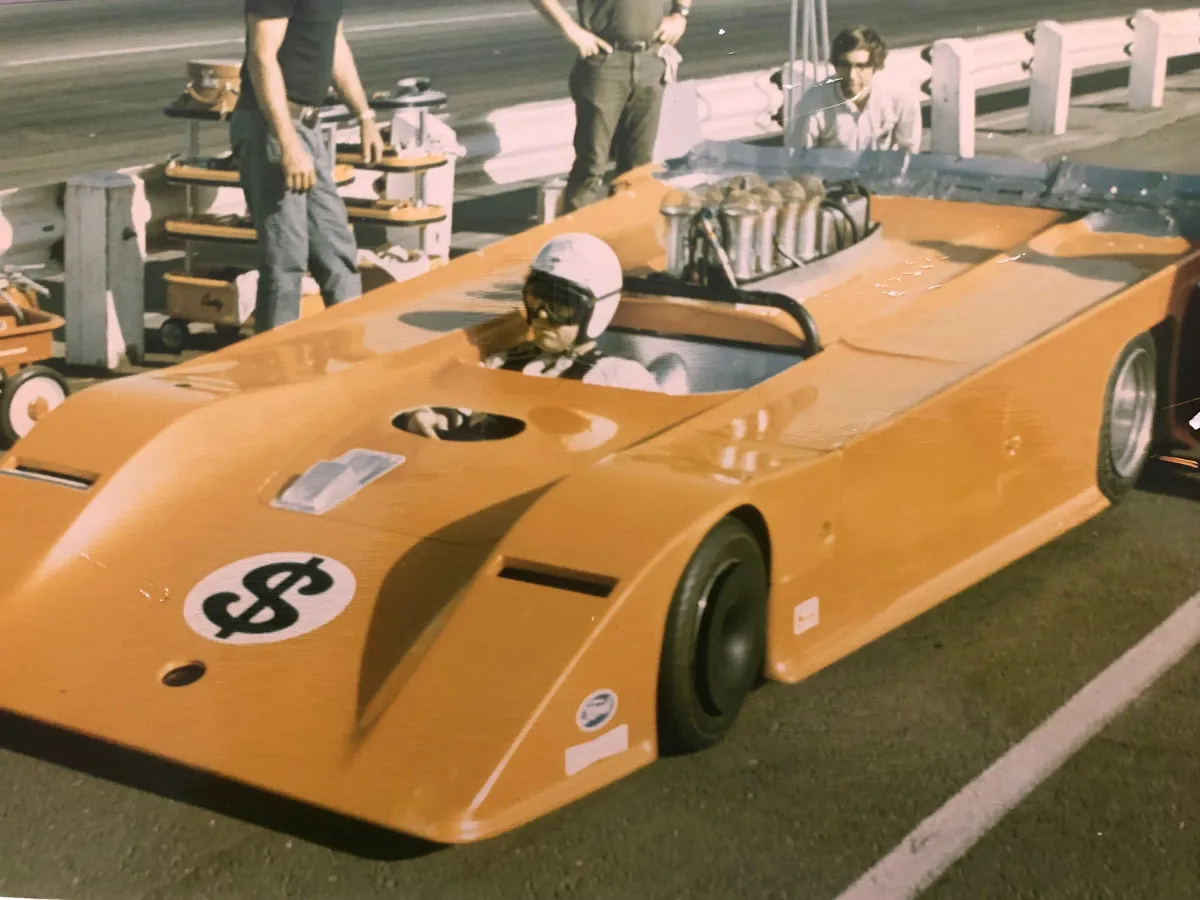

Walter Boyd, 89, is a design engineer with numerous patented industrial inventions to his credit. He is also a former race car driver and race car builder whose career has included involvement in nearly every class, from Midgets to Formula 1. Below are a few random pictures from the past.

Walter has observed the sport from different perspectives across eight decades.

For years, Walt has observed a problem for American drivers finding a pathway to achieving a career goal of one day competing in the NTT INDYCAR Series.

Below is a synopsis of the history and the thinking that led Walt to develop Formula RPD.

Prospectus for a New Racecar Class

When Walt first sat down at his computer to draft an initial design for the car he envisioned, the computer soon prompted him to save the file. With no name in mind, he saved it as the first thing that popped into his head: "Modern Midget."

As most racing enthusiasts know, Midget race cars still exist and have been modernized in some ways, especially their engines. In other respects, however, they remain not very different from how they were over seventy-five years ago.

Walt was reflecting on the role Midget racing played when he first started. For those under age 80, consider this:

In the years surrounding WWII up until the early sixties, the motorsports landscape was very different. INDYCAR racing—then known as Championship Racing—and especially the Indianapolis 500, represented the absolute pinnacle of American motorsport.

Back then, "Champ" car racing was more closely related to short-track oval racing than to road racing. The cars were much like Midgets and Sprint Cars, just larger, and they competed on similar dirt and paved tracks, albeit bigger ones.

Right after WWII, Indianapolis was the only paved track on the "Championship Trail"; all the others were dirt. This changed as more of the original horse tracks were paved. Champ cars became more specialized as the "INDY roadsters" took over on pavement. Yet, the connection between Midgets, Sprints, and Champ cars remained because they were all front-engine cars with non-independent suspension and an upright seating position.

Midgets were crucial in the broader ecosystem as a primary source of new talent for Champ car racing. After the war, the Kurtis Kraft-Offenhauser ("Offy") became the premier car, and to compete at the top level, especially on larger tracks, you needed an Offy to be competitive. However, "non-Offy" clubs also existed, typically running on smaller dirt and paved tracks, and they featured plenty of talented drivers. In today's terms, those clubs might be called "entry level."

At the other end of the spectrum, while not officially "big time," top-level Midget racing wasn't far from it. Some of the country's most revered drivers were Midget drivers, and many INDYCAR drivers continued to race them. This level featured a great depth of talent, with Midgets running on small 1/5 to 1/2-mile tracks as well as paved and dirt mile tracks.

As far back as 1947, Midgets lapped Langhorne Speedway (a circular dirt mile in Pennsylvania) at over 100 mph, sideways the entire way! They even occasionally ran road courses. Two-time INDYCAR champion Roger Ward defeated the cream of American road racers in an open competition at Lime Rock Park in 1959 with an Offy-powered Midget. (Lime Rock was uniquely suited to a "one-gear" Midget due to its short straightaway and lack of very tight turns.)

In the immediate post-WWII era, Midget racing was the highest-paid attendance sport in America, bigger than Major League Baseball. There were plenty of cars; you could get an older non-Offy Midget for the modern equivalent of a few thousand dollars. One didn't have to be rich to enter the sport or even to own an Offy. Walt knew Offy owners who weren't wealthy; they worked ordinary 8-to-5 jobs, prepared their cars in a single-car garage, and towed them on an open, single-axle trailer behind the family car.

Typical trailers had two tire posts—one for pavement tires and one for dirt—as teams often ran a pavement race one day and a dirt race the next.

Ambitious and talented Midget drivers knew that if they excelled in the top ranks, they had a shot at Champ cars, often preceded by a stint in Sprint Cars.

This all changed in the early sixties when rear-engine designs from Europe proved superior at Indy and other paved tracks. By the end of the decade, the "upright dirt cars" and Indy roadsters were gone, and all dirt races on the Championship Trail had been replaced by road races. The connection between Midgets, Sprints, and INDYCAR was severed.

Road racing eventually replaced short-track racing as the primary source of talent for INDYCAR, which created a problem.

While top-level road racing can attract large spectator turnouts and TV coverage, its lower levels are not very "fan-friendly" and are inherently expensive, partly because they require a lot of real estate. Road courses are not suitable for "Saturday night" racing under lights. As a result, lower-level road races are essentially amateur, non-spectator events. Without spectators, drivers get no fan recognition and sponsors see no return. Without "front gate" revenue, there is typically no purse, so the sizable costs of road courses are covered by high entry fees.

Once the nexus between INDY and short-track racing disappeared, short-track classes gradually evolved into separate dirt and paved divisions. Today, there are many classes of race cars, including both open-wheel and stock cars. But despite this variety, something is missing, especially on the open-wheel side: an affordable class that enables an aspiring driver to work toward the top echelon of open-wheel racing, INDYCAR.

This lack resulted in a farm system called the Road to Indy, a ladder system consisting of USF2000, INDY Pro 2000, and INDY NXT (formerly Lights). The SCCA also has the Formula 4 United States Championship.

While these developmental classes build skills and provide recognition within the road racing world, they are prohibitively expensive for all but a very small percentage of aspiring racers. This is a problem for drivers without wealthy families and for the sport itself. Drivers graduating to INDYCAR through these classes have little to no following among the huge number of short-track fans. This, Walt believes, is why INDYCAR lacks the fan base it deserves given the quality of its racing.

Furthermore, unlike their counterparts in NASCAR or predecessors in Championship racing, these drivers rarely appear at short tracks because they have no roots there, which is detrimental to both the drivers and the sport.

The Best Drivers Were Masters of Different Cars and Tracks

There is ample evidence that gaining "seat time" by competing in different types of racing creates great drivers. Versatility was a key attribute that made drivers like Mario Andretti and A.J. Foyt household names; they won at Indy, Daytona, Le Mans, and on dirt tracks, road courses, and superspeedways in Midgets, Sprint Cars, Championship cars, sports cars, stock cars, and Formula One cars.

Today, Kyle Larson and Christopher Bell are among the most exciting drivers because they win on Saturday night in Midgets and Sprint Cars on dirt and dominate in NASCAR stock cars on Sunday. Versatility isn't everything, but it creates tremendous excitement.

Walt's objective is to create a class for the modern era of open-wheel racing that serves the same purpose Midgets did seventy years ago.

What, specifically, are the requirements for such a class—working title Formula RPD?

Requirement 1: A small, open-wheel car relevant to contemporary INDYCAR.

To provide applicable experience, the car must feel and respond like an INDYCAR, both in driver feedback and in its response to chassis adjustments (which differ significantly from those of front-engine oval track cars). It must be symmetrical (not offset), rear-engined, with independent suspension front and rear, adjustable front and rear wings, and a narrow cockpit with a reclined seating position where the driver's feet are level with or higher than their seat. It must have a multi-speed transmission, a limited-slip differential, and likely a data acquisition system. To attract young drivers and spectators, it must also look contemporary.

Requirement 2: A car suitable for paved ovals, dirt ovals, and road courses.

It is vital for drivers to get significant "seat time" by racing nearly every week during the season. For a sanctioning body to book a full season within a reasonable geographic area, the cars must be able to compete on all available venues, including dirt tracks.

Furthermore, most top drivers agree that competing on different track types creates more well-rounded drivers.

Short-track racing requires a roll cage for driver safety and to meet track insurance requirements. Oval track racing involves contact with other cars and walls, so the cars must be rugged, especially on rough dirt tracks, and need bumpers and nerf bars.

Dirt track racing requires faster steering than road racing, so the steering ratio must be easily adjustable. Dirt cars also need significant steering lock (turning radius), which most formula-type cars lack.

On many small, paved ovals, the "groove" is narrow; wider cars limit outside passing and side-by-side racing. Dirt track racing favors a shorter wheelbase than most formula cars have. Consequently, this class needs to be somewhat shorter and narrower than formula cars of similar weight and power, with rules that maintain reasonable parity across all three venues.

Requirement 3: A car that is fast and powerful enough.

Racing difficulty does not automatically increase with speed, but costs and consequences rise exponentially. We believe there is a "sweet spot" where racing is challenging for skilled drivers on a variety of tracks, yet remains reasonable in cost and risk. For this car, that spot is a weight-to-power ratio of about 5:1 (including driver), with a top speed of around 150 mph.

Requirement 4: An economical car where prohibitive cost factors are minimized.

Cost factor #1: Tires. This cannot be solved by design alone and must be addressed in the rules (discussed later).

Cost factor #2: Engines. Next to tires, engines are the biggest cost driver. The concept uses Japanese motorcycle engines (the prototype uses a Kawasaki ZX14). These are readily available from salvage yards, reliable, and sophisticated enough that heavy modification yields diminishing returns. The engine, gearbox, and clutch are an integrated, affordable unit.

Cost factor #3: Travel. A car that runs on ovals and road courses allows a sanctioning body to schedule races within a small geographic area, drastically reducing travel costs.

Cost factor #4: Support personnel and equipment. Small race cars are less expensive to run. They require less shop space, can be transported on a less expensive trailer towed by a more fuel-efficient vehicle, use less fuel and fewer (less expensive) tires, and don't require a large pit crew.

Cost factor #5: Poor rules and engineering. Certain design features and rules can unnecessarily increase operating and repair costs. Walt sought to control costs through good initial design:

Chassis: A tube frame with a roll cage was chosen over a monocoque. It is adequate for the intended speeds, less expensive to build, less vulnerable to localized damage, and easier to repair.

Crashworthiness: The car is designed so a minor crash typically damages only a suspension "corner," not the frame or more expensive components.

Shocks: Shock absorbers are mounted inboard for protection. Unique actuating rockers allow for the use of longer-stroke, typically less expensive, shocks and springs.

Differential: A Quaife limited-slip differential is used. This avoids the expense of needing a large inventory of tires for rear stagger, as required in classes with locked axles.

Wings: A custom aluminum extrusion simplifies wing manufacturing, making replacements inexpensive.

Bodywork: Fiberglass body panels are modular for economical shipping and can later be made from more durable high-impact plastic.

Steering: A custom, purpose-built steering gear allows for easy ratio changes without the need for steering quickeners or time-consuming bump-steer adjustments.

Requirement 5: A rules package that prevents electronic traction control.

Traction control reduces the role of driver skill and hinders the accurate evaluation of young talent. The plan is to supply the car with a mandated ECU that allows adjustments to ignition and fuel mapping but has no traction control capabilities, paired with a wiring harness that makes it difficult to hide illegal devices.

Basic Concept of Rules

The car's design alone cannot define the class; rules are essential. While totally "spec" classes are in vogue to "level the playing field," they often stifle innovation and setup expertise, leading to rampant cheating. In our view, fewer rules are better. Key areas that must be controlled include:en if high-tech shocks provide a significant advantage in short-duration races over modern, more affordable units.

Tires: This is the foremost problem, as fresh tires always provide an advantage. There must be a spec tire, likely a harder compound for longevity. The exact tire rules will require more testing before a final recommendation.

Engines: Engine rules are difficult to enforce. The tentative plan is to allow any modification to the cylinder head (cams, valves, ports, etc.) while the rest of the engine remains stock. This would be effectively enforced by a mandatory RPM limiter in the ECU. This approach would limit the cost of a top engine to about $8,500, while a $4,500 salvage engine could often be competitive.

Weight: A minimum weight with the driver is essential. The prototype weighs 950 lbs without fuel. A tentative minimum weight, including driver, is 1,125 lbs. A weight parity may be established for the smaller, earlier version of the ZX14 engine.

Shocks: Shock technology can be extremely expensive. It remains to be seen if high-tech shocks provide a significant advantage in short-duration races over modern, more affordable units.

Initial Cost of the Car

We estimate the initial cost of a new car, less engine and tires, will be about $60,000. While this is significant, it is low compared to most race cars. After a few seasons, used cars will be available for less, making entry into the class more accessible. The initial cost is also tied to tooling investment; with more capital, this price could be substantially reduced.

A Final Thought About Formula RPD

Walt has presented Formula RPD as a pathway to INDYCAR, and as a development class, it would be an excellent and affordable way to build foundational skills.

However, driver development is not its only purpose. Think of it not primarily as a development class, but as a great racing class that should exist and, for some reason, doesn't. There is no other class like it.

For young drivers coming from karting with open-wheel ambition but limited funds, there is no other place to go where you even have a shot.

For the 25- to 45-year-old crowd who always wanted to race and now have a good job and some discretionary income, where else can you go to race a real car across such a wide spectrum of the sport?

For successful racers looking to step back from professional pressures but still race for fun, what better place to compete with serious racers and experience other forms of motorsport they may have never tried?